Sine and Cosine

By Rachelle Larsen

We ride the roar of eight cylinders, orange sand frothing around the massive tires of our rented Rubicon, our bodies bouncing to the rhythm of tire-stained boulders. I’m thrown to the right, and I smash my arm against the window. To check for damage, I start waving my hand back and forth to the beat of the engine like I’m saying goodbye. My best friend James and I are off-roading the Chicken Corners Trail in Moab to celebrate my birthday.“How’s your wrist? I saw you hit it pretty hard.”

James is staring straight ahead at the miles of ragged, burnt desert, his neck stiff from always—always—looking forward, even when the Jeep jerks him towards me, or me towards him. Even when I wish our eyes would meet. Even when he speaks to me, as he does now.

“It’s fine…” I say. “Something’s just not quite in place.”

“That doesn’t sound good.”

“Do you know what also doesn’t sound good? Morty.” I stop waving, ignoring the wrongness in my wrist. It doesn’t hurt, exactly. It just feels stiff. Like James’s neck. Or strained. Like Morty’s revving engine. “Or have we just been listening to dubstep this whole time?”

In the corner of my eye, James’s face folds into his slow smile, like he’s a crane origami filling with someone else’s breath, and I can’t help but smile too. “Morty is just a talented musician, and nice too. He’s wishing you a happy birthday.” James pats the center console. “Maybe I’ll sell my car and just take Morty to grad school instead. Or just sell my car so I can still afford higher education. Off-roading is expensive.”

“Hey, you didn’t even ask me if I wanted to go off-roading. Today is as much for my birthday as for your graduation.”

“Well, yeah. But I knew you would love it too.”

We continue driving, and inertia rules us. James has greater mass, so every time we jerk left or right, he moves just a little bit slower than me. The ends of my hair almost touch him when they swing across the center console, but then we bounce back to our seats again, and my seat belt bites into my chest, tracing a line over my heart. And as we bounce again, I bounce quicker, but he bounces longer.

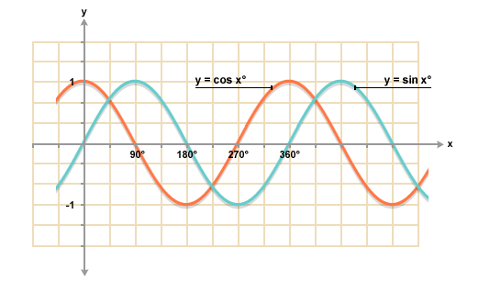

We are sine and cosine, following the same motion but slightly off of one another.

Cosine and sine are mathematical models common to the world of physics. On a graph, they look like waves, and, accordingly, they are an easy way to describe different kinds of lulling, repeated motion. As a student of physics, I have used cosine and sine to describe the music of voices, the tides of oceans, the rocking of cribs: anything with a rhythm at all.

Arguably, all these patterns can be modeled by a sine wave alone. Fourier transforms are built on this principle of using only sine waves. If you stretch, grow, shrink, shift, and sum a series of sine waves, you can describe anything. The more complex the motion, the more difficult the description becomes, but, nonetheless, it is possible. With enough data, physicists can quantify a sigh, a laugh, a question, a heartbeat, a beaten drum, a drum still beating, or even a slew of those noises clambering over each other in a crowded room.

All these phenomena can be described by sine alone because cosine itself is just an echo or an omen of a sine wave; depending on your point of view, a pure cosine is either slightly ahead or slightly behind its counterpart. In the world of cosine and sine waves, the beginning is an arbitrary position, like the chicken and the egg conundrum. It’s like standing in a hall of mirrors, watching yourself repeat both forwards and backwards, the outermost copies of yourself fading slowly into the dark.

So why do we keep cosine? Why does it exist at all?

Essentially, solutions are more elegant, more beautiful, in a system where cosine is an option for expression. The concept of slightly off, not quite the same, just not quite in sync, is so prevalent in our world that we have made a mathematical model for it: the relationship between sine and cosine.

James and I have always been sine and cosine. Like when I broke up with my fiancé as James found a girlfriend, and again when he returned that girlfriend’s ring as I had resigned myself to losing him. The motions of our lives never synced, always following parallel cycles, never moving closer together. And yet, we always end up back at his apartment, listening to the popping of hot oil as we cook a new exotic dish with our favorite flavors—mayonnaise for him (ew), and curry for me—him at the grill and me at the cutting board, music and spices wafting between us.

We find ourselves together just in time to drift apart. It may take months, but inevitably, we separate. Sometimes I lead the separation, sometimes him, but it always happens.

It may take months again, but inevitably, we come back together. Sometimes I lead the reunion, sometimes him, but it always happens.

Sine and cosine, back and forth, apart then together.

Is there a point to relationships with no climax? Is there value to cycles? Are cycles always something to escape? Can you progress while still following a cycle?

I like to think so. The constants in life provide the foundation for growth in other areas, and a cycle is just a spiced-up constant. Like how the moon circles around the earth, pulling the tides and thereby allowing for life to exist. It is a cycle, a stability, and a blessing.

But cycles can feel shiftless and wandering. They can leave you feeling restless and unfulfilled. A cycle in and of itself can feel stagnating if there aren’t other positive externalities. If the moon didn’t create the tides, would its cycle be worth anything? Or would its worth come from its aesthetics? The slow waning and waxing of the moon is a subtle, creeping beauty, and I believe the nighttime sky would be worse off for its absence.

“I don’t think any of these look like Chicken Corners.” James hesitates an hour or two into our drive.We are passing narrow pass after narrow pass, but none exactly match the description in our trail guide. “And it’s definitely getting darker outside.”

The orange sand is a deeper color now, almost red. “Just a little further,” I say. And so he drives faster, trying to outpace the sun so we can see Chicken Corners before we head back. The Jeep groans under the stress; it sounds like breaking submarines that I’ve seen in movies, and we bounce even more: back and forth, up and down, rocking, rocking, rocking, the drizzling sky leaking in through the sunroof.

I think I see Chicken Corners. I sit up straighter, peering over the dashboard at the shadowy, thin path ahead. But then James puts the Jeep in park, and Morty falls silent.

“It’s getting dark, and I want to be out of here before the sun sets. This is Chicken Corners, even if it isn’t.” He slides out, and I follow him—I’m the slower one this time—to the edge of the cliff. Beneath us, the Colorado river sprawls out like a forgotten shoelace.

“Wow,” I breathe.

“It’s so quiet,” he responds. “You can hear the river.”

Shhh, the river croons from a mile away, shhh. But my ears ache. They crave noise. In this silence, I can almost hear my quickening heartbeat. I can hear the crunch of gravel as James shifts his weight towards me. I can hear us breathing. He breathes in as I breathe out, and I wonder if he’s smiling again, and if it’s because of me, and if we’re playing catch with the air rather than the words we could say: words that we can finally say, because there is nothing else to hear. It’s just us, the drop-off, and miles of silence.

We stand as if we’re waiting for something—An angel? A mudslide? A conversation? I want to take his hand as we wait for it. I want to smooth the wrinkle lines around his eyes with my thumb, cup his face with my hand, and feel his smile fold beneath my palm. I want to meet his gaze and smile because—finally—we are not cosine and sine anymore.

Nothing happens.

James comments on the darkness, and we slide back into our Jeep. “That was fun,” he says. “Maybe I can come back on break from grad school, and we can do it again.”

I sense him looking at me, but I don’t turn to him. “I don’t know if I like off-roading after all. It’s not safe.” I wave my hand back and forth again because the pain in my wrist from earlier feels better this way. “And I’m starting to get a headache from all the jerking around.”

“I’m sorry about your wrist and your head.” James looks back to the road. “I would fix it if I could.”

The engine fills the silence, growling back to life, and we rock to our same old rhythm. Happy birthday, happy birthday, Morty whines again, but there are no candles and no wishes, no curry and no music. There is just the smell of orange sand, the color of it faded to dark red in the sunset, like a rusting swing.

My neck aches from staring straight forward, even when the Jeep jerks me towards James, and as Chicken Corners fades away behind us, I realize that I’m still waving goodbye.

So why do we keep cosine? Why does it exist at all?

Essentially, solutions are more elegant, more beautiful, in a system where cosine is an option for expression. The concept of slightly off, not quite the same, just not quite in sync, is so prevalent in our world that we have made a mathematical model for it: the relationship between sine and cosine.

James and I have always been sine and cosine. Like when I broke up with my fiancé as James found a girlfriend, and again when he returned that girlfriend’s ring as I had resigned myself to losing him. The motions of our lives never synced, always following parallel cycles, never moving closer together. And yet, we always end up back at his apartment, listening to the popping of hot oil as we cook a new exotic dish with our favorite flavors—mayonnaise for him (ew), and curry for me—him at the grill and me at the cutting board, music and spices wafting between us.

We find ourselves together just in time to drift apart. It may take months, but inevitably, we separate. Sometimes I lead the separation, sometimes him, but it always happens.

It may take months again, but inevitably, we come back together. Sometimes I lead the reunion, sometimes him, but it always happens.

Sine and cosine, back and forth, apart then together.

Is there a point to relationships with no climax? Is there value to cycles? Are cycles always something to escape? Can you progress while still following a cycle?

I like to think so. The constants in life provide the foundation for growth in other areas, and a cycle is just a spiced-up constant. Like how the moon circles around the earth, pulling the tides and thereby allowing for life to exist. It is a cycle, a stability, and a blessing.

But cycles can feel shiftless and wandering. They can leave you feeling restless and unfulfilled. A cycle in and of itself can feel stagnating if there aren’t other positive externalities. If the moon didn’t create the tides, would its cycle be worth anything? Or would its worth come from its aesthetics? The slow waning and waxing of the moon is a subtle, creeping beauty, and I believe the nighttime sky would be worse off for its absence.

“I don’t think any of these look like Chicken Corners.” James hesitates an hour or two into our drive.We are passing narrow pass after narrow pass, but none exactly match the description in our trail guide. “And it’s definitely getting darker outside.”

The orange sand is a deeper color now, almost red. “Just a little further,” I say. And so he drives faster, trying to outpace the sun so we can see Chicken Corners before we head back. The Jeep groans under the stress; it sounds like breaking submarines that I’ve seen in movies, and we bounce even more: back and forth, up and down, rocking, rocking, rocking, the drizzling sky leaking in through the sunroof.

I think I see Chicken Corners. I sit up straighter, peering over the dashboard at the shadowy, thin path ahead. But then James puts the Jeep in park, and Morty falls silent.

“It’s getting dark, and I want to be out of here before the sun sets. This is Chicken Corners, even if it isn’t.” He slides out, and I follow him—I’m the slower one this time—to the edge of the cliff. Beneath us, the Colorado river sprawls out like a forgotten shoelace.

“Wow,” I breathe.

“It’s so quiet,” he responds. “You can hear the river.”

Shhh, the river croons from a mile away, shhh. But my ears ache. They crave noise. In this silence, I can almost hear my quickening heartbeat. I can hear the crunch of gravel as James shifts his weight towards me. I can hear us breathing. He breathes in as I breathe out, and I wonder if he’s smiling again, and if it’s because of me, and if we’re playing catch with the air rather than the words we could say: words that we can finally say, because there is nothing else to hear. It’s just us, the drop-off, and miles of silence.

We stand as if we’re waiting for something—An angel? A mudslide? A conversation? I want to take his hand as we wait for it. I want to smooth the wrinkle lines around his eyes with my thumb, cup his face with my hand, and feel his smile fold beneath my palm. I want to meet his gaze and smile because—finally—we are not cosine and sine anymore.

Nothing happens.

James comments on the darkness, and we slide back into our Jeep. “That was fun,” he says. “Maybe I can come back on break from grad school, and we can do it again.”

I sense him looking at me, but I don’t turn to him. “I don’t know if I like off-roading after all. It’s not safe.” I wave my hand back and forth again because the pain in my wrist from earlier feels better this way. “And I’m starting to get a headache from all the jerking around.”

“I’m sorry about your wrist and your head.” James looks back to the road. “I would fix it if I could.”

The engine fills the silence, growling back to life, and we rock to our same old rhythm. Happy birthday, happy birthday, Morty whines again, but there are no candles and no wishes, no curry and no music. There is just the smell of orange sand, the color of it faded to dark red in the sunset, like a rusting swing.

My neck aches from staring straight forward, even when the Jeep jerks me towards James, and as Chicken Corners fades away behind us, I realize that I’m still waving goodbye.

Comments